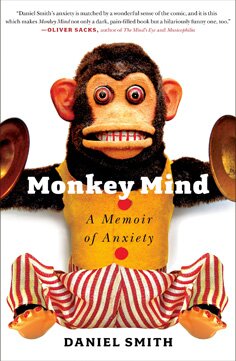

monkey mind (mung ke mind) n. A state of being in which the thoughts are unsettled, nervous, capricious, uncontrollable. [Chinese xinyuan, Sino-Japanese shin’en]

Monkey Mind is a tragicomic memoir about anxiety — both the emotion, which is universal, and the clinical condition, which is rampant. Mostly it’s about the clinical condition. It’s about anxiety so acute and chronic that it permeates every waking moment, affecting your body and mind, your friendships and relationships, your work and your will.

Write what you know, they say.

I’ve known anxiety for most, maybe all, of my life. The condition is genetic. My father was anxious. My mother was anxious. My grandparents were anxious. Probably my ancestors were all anxious. My last name is Smith, but this is what’s known as an “Ellis Island name” — something the authorities gave my great-grandfather when he arrived in the early twentieth century. The original family name is Gomolski.

In other words, we’re Jewish. There is no race or ethnic group on Earth that does not suffer from anxiety. But Jews are particularly good at that kind of suffering.

I didn’t know I was anxious until I was a teenager. Before that, I was “sensitive” and “nervous.” I had phobias and tics and sudden fears. Then, when I was sixteen, I lost my virginity under odd, unfortunate circumstances (see the book; it’s a cool story), and my anxiety began to take over my life. Monkey Mind tells how that happened; the troubles and difficulties that followed over the coming years; and the many attempts, wise and unwise, I have made to alleviate my anxiety.

Notice: alleviate, not cure. Anxiety isn’t a condition like pneumonia or chicken pox. It isn’t something you can eradicate. It’s a state of being, a coloration in the way a person thinks, feels, and acts. It isn’t a disorder, necessarily, though it can be exquisitely painful and it does sometimes stem from trauma. What it is, is a state of mind. It can be reduced, in some cases radically, but it never totally goes away.

What I set out to do in Monkey Mind was to describe and explain the experience of anxiety. Anxiety is often spoken of in cultural and collective terms: we are living, it is said, in an “age of anxiety.” But what does anxiety feel like? How does it affect everyday life? Kierkegaard, who was maybe the most anxious person ever to live, described anxiety in this way:

And no Grand Inquisitor has in readiness such terrible tortures as has anxiety, and no spy knows how to attack more artfully the man he suspects, choosing the instant when he is weakest, nor knows how to lay traps where he will be caught and ensnared, as anxiety knows how, and no sharpwitted judge knows how to interrogate, to examine the accused, as anxiety does, which never lets him escape, neither by diversion nor by noise, neither at work nor at play, neither by day nor by night.

What does it mean for a person to have to deal — day after day, night after night — with that Grand Inquisitor in her head?

The short answer is: It isn’t fun. The long answer is this book.

So then why tragicomic? Because for all the pain, anxiety is an inherently comical disorder. It destroys lives, but it destroys them with absurdity. To witness a person in the throes of true anxiety is to witness a person actively tripping himself, a person whose sane faculties — the ability to reason and recognize threat, the capacity to apply logic — have grown to monstrous, B-movie proportions. Anxiety is the intellect gone feral. Also, to treat anxiety as an absurd state of mind is to declaw the experience and reveal its pettiness. Anxiety can indeed destroy relationships. It has destroyed some of mine. But it can do so only when the sufferer treats it with blind seriousness, when he treats it as applicable to meaningful bonds and meaningful decisions. Yet anxiety doesn’t care what its object is: it’s ecumenically corrosive. In the grip of anxiety, a sufferer is capable of reasoning himself not just out of marriage but out of lunch. On more than one occasion anxiety has paralyzed me over a salad, convincing me that a choice between blue cheese and vinaigrette is as dire a choice as that between life and death. Once this is recognized, anxiety loses some of its power.

This is what Monkey Mind is designed to accomplish. I have written with sheer honesty about the self-destructive absurdities, both major and minor, into which anxiety has led me. The goal is to expose anxiety as the pudgy, weak-willed wizard behind the curtain of dread. The goal is to tame what has always seemed to me, and to the tens of millions of others who suffer from anxiety, as a horrible, sharp-fanged beast.

Essay providers with free essay extender tool at WriteMyEssay deliver academic content designed to meet both subject requirements and submission deadlines.